The essence of being human is often reflected in the traces we leave behind. Our interactions with others, the physical marks we make on the world, the cultural and artistic contributions we create, and the memories we leave in the minds of those we encounter—these traces take many forms. Our very existence is confirmed by the impressions we make. What we leave behind paves the way for future generations to understand and appreciate the lives we have lived and the world we helped shape.

When we are young, we learn to tell stories through our drawings: “Draw a scene describing activities you did during the summer break.” The drawing may contain a yellow circle with spikes all around it—the sun. Wavy lines stacked with spaces in between them—the ocean. Figures with their arms extending in the air and crescent smiles—the family having fun. Decades later, when admiring the artwork, you can determine the mood, the season, and the event taking place. Whether you were there in person or not, you can connect with the human who drew it and the environment the drawing conveys.

Petroglyphs: Capturing The Human Story

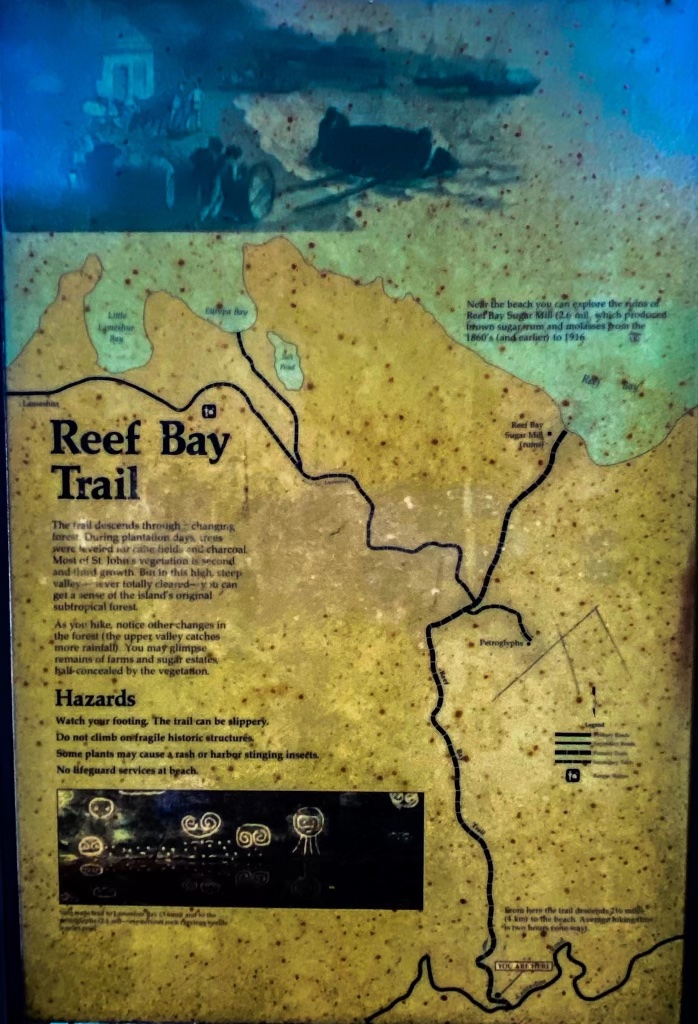

Before traveling to St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands this past winter, we prepared for our visit by reading about the island’s history and its pre-Columbian era when the island was inhabited by the Taino people. Our love for hiking and connecting with the natural world led us to the Reef Bay Trail at Virgin Islands National Park, where you can find petroglyphs.

Reef Bay Trail is a back-country trail, 4.4 miles in-and-out, with a descent down to a beach and a 900 ft. elevation gain on the way back up. While it’s a strenuous hike with some uneven terrain and rocky areas (we recommend a light daypack, water, hat, closed-toed hiking shoes, eco-friendly mosquito repellent, and sunscreen), it’s an incredible way to slowly descend down the island and find yourself back in time, into another world yet still within our world.

Along the trail, there were incredible plants and vegetation, some of the oldest and tallest trees on the island such as the Genip Tree, an evergreen tree native to South America that produces a tartly sweet fruit eaten by the locals. We greeted a giant West Indian Locust, a tree found throughout the West Indies and parts of Mexico and South America. The West Indian Locust produces a large, dark red seed pod that contains seeds surrounded by a strong-smelling yellow pulp, which gives the tree its name “stinkin’ toe tree.”

You can eat the pulp, and we were fortunate to taste the delicious sweet pulp while visiting a small beach on St. Thomas where the locals frequent. There, we met and spoke with a 70-year-old vegan man whose family lives on the island but originated from Kenya. He and his grandchildren own and operate a beach hut plant-based smoothie bar. We were gifted a sample West Indian Locust seed pod that the family was going to use to make a plant-based ice cream.

As we continued our descent down the Reef Bay Trail, passing through the dilapidated sugar plantations owned by Dutch colonists, it was apparent that an all too familiar human history was about to present itself to us. Prior to European colonization, the island was occupied by Taino and Caribe peoples, according to confirmed archaeological research. Passing through the plantation sites left us with an edified impression of colonialism: slave and forced labor, environmental degradation, and exploitation.

“After official colonization of St. John it took only 15 years for the Danish West India and New Guinea Company to establish 109 sugar, cotton and provisioning plantations with the labor of over 1,000 enslaved Africans; and a primarily absentee European planter population.” – cited from an article published by the National Park Service.

Humans have an incredible ability to learn from past injustices. While we may not want to be confronted with complex and dark history, it’s important to acknowledge it as another form of a trace left behind that can help us make better decisions amongst each other in the future.

As we moved past the sugar plantations, we hiked a little further down a path that led to a small beach.

We met the calm blue ocean. There, we imagined the lives of the ancestral humans before us. Early humans arrived in the Virgin Islands from South America somewhere between 2500-3000 years ago. Archaeological evidence exists near the beaches of Lameshur Bay. Around 1000-1300 years ago marks the arrival of the Taino people.

The Taino had a very complex society and spoke an Arawakan language, commonly spoken in a number of areas that are now Cuba, the Bahamas, and some parts of Brazil from the mouth of the Amazon to the mountains of the Andes before the Spanish conquest. Taino is a now-extinct Arawakan language and was one of the first Native American languages to be encountered by Europeans. In fact, the word hammock was derived from the Taino word hamaca—a sling made of fabric, rope, or netting, suspended between two points.

From the beach, we started our ascent back up through the trail. Along the path, we found the wild pineapple, Bromelia pinguin, that grows near the ruins, serving as barrier hedges and living pasture fences. The thorny saw-toothed plant yields a tasty fruit that is rich in Vitamin C. You can eat the juicy pulp inside of the ripened yellow fruit husk. The outer part of the husk could irritate your skin, so proceed with caution. We gave it a taste, and it didn’t disappoint!

After a boost of Vitamin C, we took a left turn on the path to commence the short distance to the petroglyphs. Walking through the tree canopy-covered path felt surreal, timeless, and familiar. It was quiet and serene—just the two of us and the feeling that we were walking into history.

At the end of the path was the beginning of a time period. A time when the Taino people may have gathered together, near the pool of water that was fed by a waterfall glistening over the rocks. Water, the source of life.

At the base of the waterfall are the traces, the artwork, the essence, of humans. Humans, capturing a story, a scene, or a moment. We put ourselves into the mode of the observer and visitor. From that view, one can be transported back but also connect in the present.

The petroglyphs were carved here at Reef Bay and other water sources, according to archaeologists. Researchers believe that the carvings near water are significant to the Taino beliefs in duality between the natural and supernatural worlds, as the water acts as a mirror reflecting between the two, a connection to the ancestral past. Incredibly, identical carvings are found throughout the Caribbean, linking worlds together and evoking a sense of connectivity.

Petroglyphs capture the essence of human beings, particularly creativity, communication, and connection to the environment.

They are a testament to human creativity and the desire to express thoughts, ideas, and experiences visually. The effort and skill involved in creating these carvings highlight the artistic inclinations of early humans.

Carvings represent early forms of communication, serving as a means to convey stories, beliefs, and important information across generations. The use of symbols and images allowed ancient peoples to share knowledge and experiences in a way that could be understood by others, even long after the original creators were gone.

The content and location of petroglyphs often reflect a deep connection to the natural world. They frequently depict animals, human figures, and natural elements, illustrating how early humans observed and interacted with their surroundings. The choice of rock surfaces and specific sites for these carvings also suggests an awareness of the landscape’s significance.

By creating petroglyphs, early humans, such as the Taino, left a lasting legacy that continues to speak to us today. These carvings serve as a bridge between the past and the present, allowing modern-day people to connect with and learn from ancient cultures.

In these ways, petroglyphs capture fundamental aspects of what it means to be human. They reflect our innate drive to create, communicate, connect with our environment, seek understanding, and leave a mark on the world. While they are not the entirety of the human essence, they are a powerful and enduring expression of it.

During our travels, we aim to connect and learn from our human history and find answers to the question, “What does it mean to be human?” For us, a hike on St. John’s Reef Bay Trail showed us that to be human is to learn to be present while walking in the path of your past.

Thank you for reading,

William & Davita

Want to dig deeper? Check out these helpful resources:

Indigenous Peoples | Virgin Islands National Park

Leave a comment